Why Eminent Domain Can't Save Broke Cities Like

Richmond, California

Emily Badger

Oct 25, 2013

http://m.theatlanticcities.com/housing/2013/10/why-eminent-domain-cant-save-broke-cities-richmond/7358/

As we've mentioned, the city of Richmond, California, recently took the drastic step of voting to use eminent domain to try to rescue underwater homeowners. Under the plan (the city has not yet actually executed it), Richmond would effectively seize mortgages from investors who currently hold them, paying about 80 percent of a home's current market value. A for-profit company working with the city would then restructure the mortgages and sell them back to the current homeowners at a rate they could afford.

The very places considering eminent domain have problems too complex to be easily solved by it.

The idea has prompted all kinds of criticism (as well as populist praise) far beyond Richmond. Banks cry that they'll have to stop giving credit to cities that show they're willing to seize mortgages. The Federal Housing Finance Agency has wagged its finger. And law professors debate whether all of this is even legal. For outsiders less interested in the housing implications or the legal theory, the story has simply been a For outsiders less interested in the housing implications or the legal theory, the story has simply been a compelling one about a hard-luck town forced to rescue its own residents when no one else would help.

But in this raucous national debate, focus on precedent may have obscured a more basic question: If this were legal, if Richmond did succeed in doing this with hundreds of homes, would it help solve the city's deep troubles?

Pamela Lee, a research associate with the Housing Finance Policy Center at the Urban Institute, argues that a constellation of problems that left Richmond so far behind during the economic recovery also mean that this eminent domain proposal wouldn't touch the roots of the city's distress. Richmond's problem isn't simply – or even primarily – that so many homeowners are underwater.

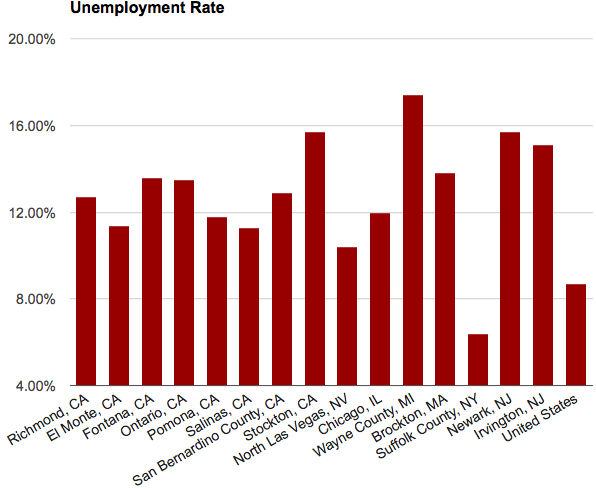

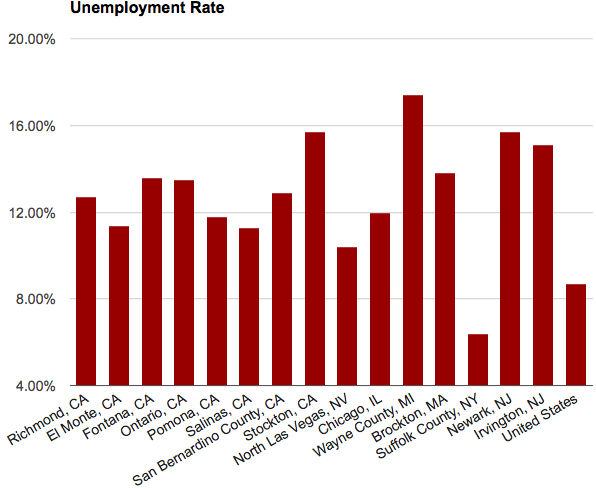

Richmond is the only city in the U.S. that has gotten this close to using eminent domain. But it is not the only city that's considered it. To understand the commonalities among all of the municipalities that have weighed this option of last resort, Lee corralled data on 15 communities that have publicly expressed some kind of interest in using eminent domain, eight of them in California, plus Newark, Chicago, and several smaller municipalities.Look at them all side-by-side, and it's clear that they suffer from some systemic and shared woes that go far beyond housing. Aside from Suffolk County, New York, every one of them had an unemployment rate above the national average (shown at far right), based on American Community Survey data from 2007-2011:

Data from the 2007-2011 ACS

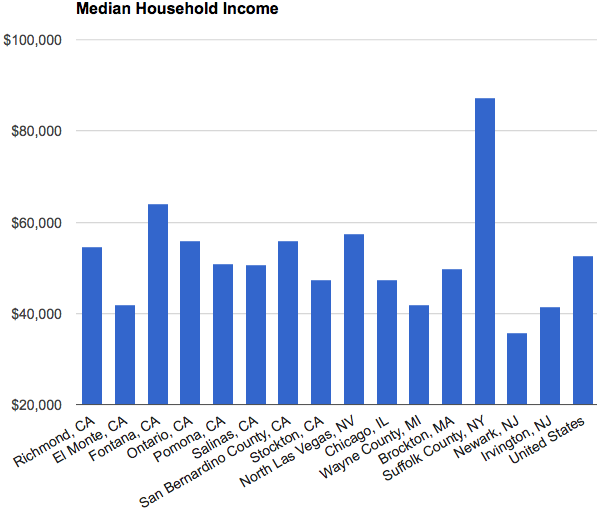

In nine counties, the median household income was below the national rate:

Data from the 2007-2011 ACS

Many of these places also have notably lower income levels than the communities immediately around them. The median income in New Jersey is 50 percent higher than it is in Irvington, and 42 percent higher than in Newark. In Richmond, it's 30 percent lower than in Contra Costa County. And in most of these places, the median income (adjusted for inflation) has also decreased since 2000, as housing vacancy rates have remained high.

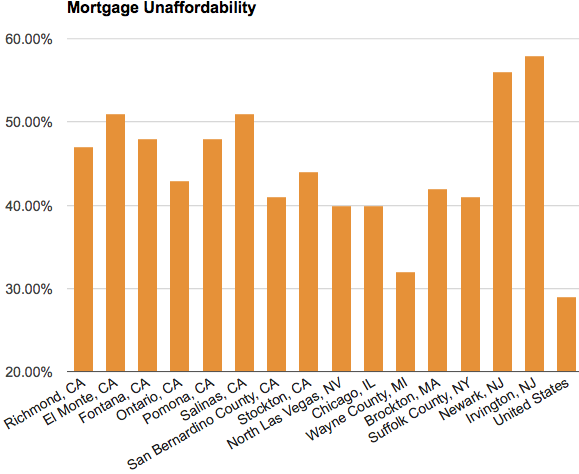

This last chart built with Lee's data shows the local share of mortgaged homeowners paying at least 35 percent of their income on housing costs, a sign that they may be struggling to keep up:

Data from the 2007-2011 ACS

These cities, in other words, were in bad shape before the housing crisis happened, they suffered particularly acutely from it as a result, and they've been the slowest to recover amid what Lee calls "a toxic combination" of high unemployment, high vacancy rates, and high proportions of cost-burdened homeowners. In effect, the very places that have been forced to consider last-ditch solutions like eminent domain have problems that are too complex to be easily solved by it.

Emily Badger is a staff writer at The Atlantic Cities. Her work has previously

appeared in Pacific Standard, GOOD, The Christian Science Monitor, and The New

York Times. She lives in the Washington, D.C. area.